When Kenya’s Deputy President, Kithure Kindiki, announced in Belém, Brazil, that international organisations were praising the country’s social housing program and the Nairobi Rivers Regeneration Project, it felt like a proud moment for many Kenyans. After all, this recognition highlighted Kenya as a beacon of hope in global climate action and urban resilience, showcasing homegrown solutions that aim to address pressing local challenges.

However, while the world celebrates these initiatives, a different conversation unfolds at home, particularly among residents in informal settlements and along the polluted stretches of the Nairobi, Mathare and Ngong rivers. The impacts of these projects can vary greatly depending on who you ask.

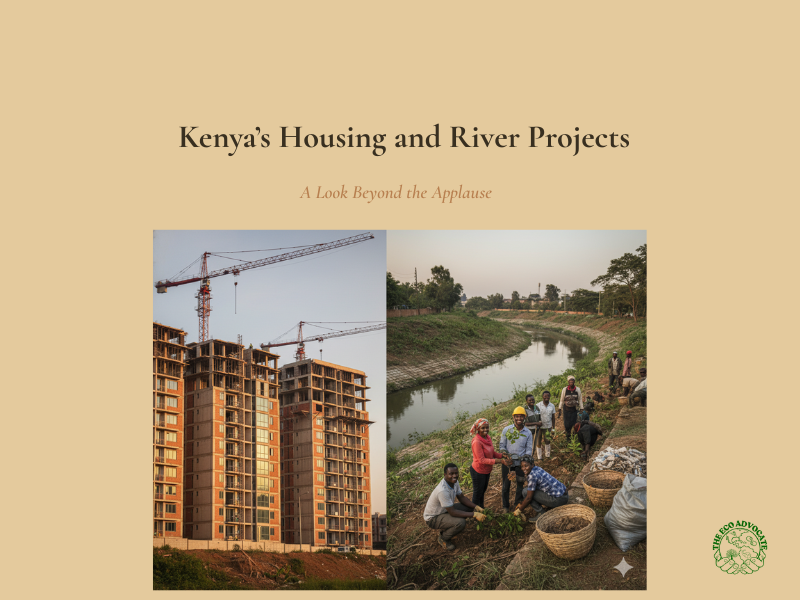

The Ambitious Vision: Housing and Cleaning Our Rivers

Launched in 2017 and expanded under President William Ruto, the government’s Affordable Housing Programme (AHP) aims to address Kenya’s critical housing deficit. With a shortage of around 200,000 housing units needed each year, and only about 50,000 being built, the need for this program is urgent.

This initiative isn’t just about providing homes; it’s interconnected with climate action. By offering better housing, the program aims to limit urban sprawl, enhance sanitation and reduce emissions that stem from inadequate waste management and energy inefficiency.

On the other hand, the Nairobi Rivers Regeneration Programme (NRRP) is a flagship initiative aimed at restoring the city’s vital waterways, which have suffered from years of pollution from industrial waste and sewage. This initiative involves various actions such as relocating households, removing illegal structures, and launching reforestation efforts, often with the support of local youth and environmental groups.

Together, these projects represent a commitment not only to infrastructure but also to social justice, promoting a vision of cities where all people, especially the urban poor, are valued as partners in building a sustainable future.

The Challenging Reality: Voices from the Ground

Despite the grandeur of these initiatives, the reality for many residents living near the rivers or in informal settlements tells a different story. Many have reported abrupt demolitions of their homes without adequate notice or plans for resettlement. Human rights organisations, including Amnesty International Kenya, have raised concerns about forced evictions in areas like Mathare and Mukuru, where families have been displaced under the guise of river restoration.

For these residents, “climate action” has felt more like a threat to their homes and livelihoods, starkly contrasting the government’s portrayal of community-led solutions. Furthermore, while the housing program has created jobs and new residential areas in locales like Kibera, Soweto B and Pangani, the challenges around housing affordability and allocation processes remain significant. Many families still find the designated “affordable” units out of reach, with prices starting at KSh 1.5 million.

The central question persists: who truly benefits from these projects?

Bridging the Gap: Global Recognition and Local Reality

At COP30, Kindiki’s announcement of the UN agencies’ commendation marks significant recognition of Kenya’s efforts in the climate dialogue. It suggests that African cities can innovate and lead in sustainable practices rather than just follow global trends. However, as we bask in this international praise, it’s essential to recognise the complex social dynamics intertwined with these projects.

Climate resilience cannot simply be evaluated by initiatives or funding partnerships; it must genuinely reflect the lived experiences of residents on the ground. If the local communities feel excluded or even harmed, the intended environmental benefits may be overshadowed by social injustice.

Kenya’s vision deserves acknowledgement, but it also calls for an honest examination of its contradictions. Real resilience comes from fostering trust and engaging communities as stakeholders, rather than delivering superficial solutions that disregard local experiences.

Moving Forward: Transforming Applause into Action

To make these initiatives truly transformative, we must focus on three crucial aspects:

- Transparent Participation: Ensure that communities living along the rivers and in low-income settlements are involved in the planning and implementation stages of projects, rather than being informed only after decisions are made.

- Social Safeguards: Develop clear and enforceable frameworks for resettlement that protect residents from being displaced under the pretext of environmental cleanup.

- Integrated Climate Planning: Recognise that urban resilience transcends construction efforts; it incorporates effective water management, efficient waste systems, job creation and governance that prioritises people’s needs.

Kenya is on the right track, promoting climate-smart housing, cleaner rivers and greener cities. Yet, the vision must be deeply rooted in integrity and comprehensive community engagement.

While the world may spotlight Kenya’s progress through impressive reports and accolades, the true measure of success will be how Nairobi’s most vulnerable residents experience these changes in their daily lives. Can they breathe cleaner air, live free from the threat of eviction and genuinely participate in building a sustainable city? Only when these hopes are fulfilled can we truly claim effective climate leadership.

Attribution:

This post responds to reporting from The Star (Kenya), November 2025, on Kenya’s recognition at COP30 for its social housing and Nairobi Rivers Regeneration initiatives.

Exactly.