On January 3, 2026, a significant loss echoed through the hearts of many in Kenya and beyond. The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) announced the passing of Craig, one of Africa’s last super tusker elephants, who died peacefully at the age of 54 in Amboseli National Park. Craig was more than just an elephant; he was a symbol of conservation success, a gentle giant adored by locals and tourists alike. His death was marked by an outpouring of tributes, illuminating how deeply conservation stories can resonate when they align with national pride and global attention.

Yet, only days earlier, in Siaya County, a starkly different story unfolded. Charles Otieno, a farmer whose dog was killed by a python, found himself grappling with a situation many rural Kenyans face: conflict with wildlife. In an act of desperation, he killed the snake and took its body, along with his dog’s, to the police station, seeking accountability and action. His protest highlighted a critical issue: the way we perceive wildlife deaths can vary dramatically depending on who is involved and the nature of the conflict.

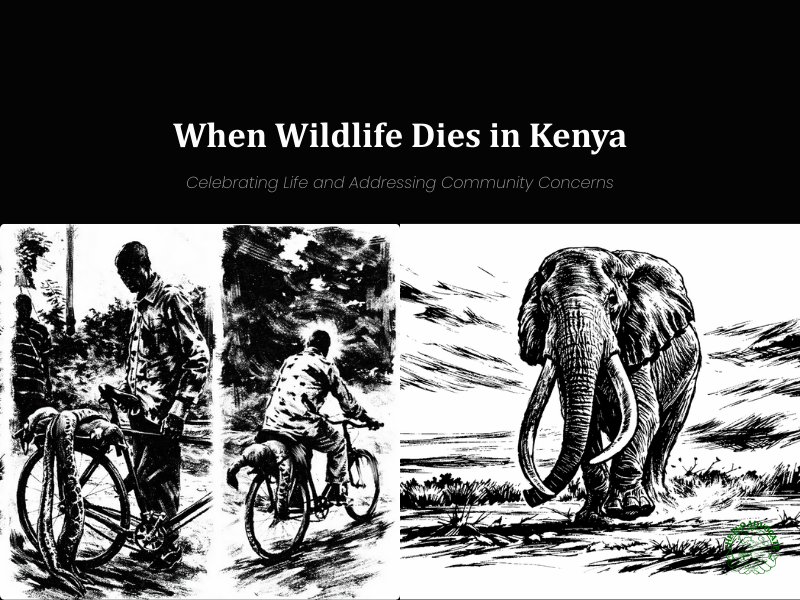

Craig the Elephant: A National Icon

Craig was no ordinary elephant. As a super tusker, with tusks weighing over 45 kg each, he represented a rare and majestic aspect of Kenya’s wildlife. The KWS and conservation partners quickly celebrated Craig’s life and legacy, portraying his death as a significant loss not only for Kenya but for the world’s natural heritage. He was celebrated as:

- A “true icon” of Kenyan wildlife and a testament to conservation success.

- A gentle giant, beloved by both tourists and researchers.

- A symbol of what determination, habitat protection, and anti-poaching efforts can achieve.

Craig’s existence became intertwined with Kenya’s tourism narrative, supported by partnerships that aimed to combine wildlife protection with national pride. The widespread media coverage and discussions about preserving his body in a museum showcased the high regard for Craig and what he represented.

A Python in Siaya: The Struggles of Everyday Reality

In contrast, the incident in Siaya unfolded quietly, away from Amboseli’s spotlight. For Charles Otieno and his neighbours, wildlife encounters are often fraught with danger and hardship. The python had become a persistent threat, killing not only chickens and goats but also a family’s domestic animals, an integral part of local farming communities.

This poignant moment, of a man riding his bicycle with two dead animals, encapsulates the everyday human-wildlife conflict faced by many rural Kenyans:

- Livelihoods at Stake: For small-scale farmers, dogs serve critical roles as protectors against wildlife threats, playing a vital part in daily life.

- Institutional Response: The bureaucratic procedures can feel slow and opaque, creating frustration for those directly affected.

- Visibility Gap: Incidents like Charles’s often gain attention only through dramatic acts, rather than through systemic recognition and support for ongoing human-wildlife conflicts.

Bridging the Gap: What These Contrasts Reveal

1. Narratives Shape Value: Craig’s story became a national narrative tied to ideas of heritage and tourism, while the python’s death gained attention only because of a protest. This highlights a selective recognition of loss within conservation discussions.

2. Charismatic Wildlife vs. Daily Realities: Conservation efforts in Kenya typically shine a spotlight on charismatic animals like elephants and lions. In contrast, conflicts involving snakes, primates, or other wildlife threats to farmers’ livelihoods remain largely underacknowledged.

3. Elite Perceptions vs. Inclusive Conservation: For many living near wildlife, conservation can feel exclusionary, emphasising global recognition over local realities. This disconnect risks sidelining everyday voices and challenges, painting conservation as an elite endeavour instead of a communal effort.

Toward a More Inclusive Conservation Narrative

Kenya’s wildlife is not just confined to national parks; it thrives in the intertwined lives of people, farms, and communities. To foster genuine conservation, we must integrate the voices of rural communities and acknowledge the challenges they face daily.

By supporting local initiatives that address human-wildlife conflicts and recognising the importance of every creature, whether celebrated like Craig or unceremoniously lost like the python, we can build a more holistic approach to conservation. This involves not only protecting the majestic animals that draw global attention but also valuing the stories and struggles of those living alongside wildlife.

As we move forward, it is essential to advocate for policies and practices that support coexistence, ensuring that every voice is heard and that wildlife conservation is a shared journey, one that embraces both the iconic and the everyday. Together, we can appreciate the richness of Kenya’s natural heritage while supporting the communities that contribute to its preservation.